It may be my Catholic upbringing--suffer first on this earth, then get your reward in heaven--but I believe that only those who have endured a northern winter can truly enjoy spring. It's not that I hate Vermont winters. I would never chosen to move here if I did, and I confess to looking a few millimeters down my nose at those who flee to warmer places at the first sign of snow.

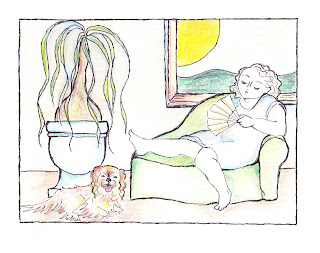

Vermont winters are beautiful in so many ways--the muted shades of the landscape after the visual brouhaha of autumn, the frigid morning air that wakes up the very marrow of your bones, the roads empty of tourists. When the days grow short I retreat indoors, along with the wild creatures. Book in hand, the cat blinking on my lap, the dog dreaming by the (gas) fireplace, I am as contented as a chipmunk in her hole. But by mid-February all this hygge begins to pall. I have been stoic for months. I have not lapsed into bitterness or self-pity. I have sat before my light therapy box every morning, and poured extra vinegar into the washing machine to minimize static cling. Now I deserve--no, the universe owes me--spring.

I'm not asking for those clichés of the full-blown season, lilacs and daffodils. I'd be grateful just to be able to go outside with only a coat on, instead of coat, hat, scarf, gloves, mittens, heavy socks, and yaktracks strapped to my boots. I'd be thrilled to rediscover the humble pleasure of walking while looking at the trees and the sky, instead of looking at the ground, on the watch for black ice. And, after months of hearing only the cawing of crows (which I nevertheless appreciate as a sign of life in the otherwise dead landscape), it would cheer my soul to hear a little brown bird singing at the top of a tall, bare tree.

What makes a northern spring so magical is not out there in the physical world, but rather inside us, in our human nature. As the troubadours, the Victorians, and the Church knew, we humans mostly hanker after what we can't have: the princess in the tower, the ankle beneath the petticoat, truffles during Lent. The grass-is-greener principle is ingrained in our neurons, alas: after prolonged exposure to a pleasurable stimulus the delight begins to fade, and we look around for something different.

Therefore, thank heaven for the four seasons, Nature's built-in mechanism to keep us happy and on our toes. Grateful as I am for every glimpse of green--and there aren't many around here at the moment--I know full well how tired I will be of the omnipresent greenery (not for nothing is this state named after les verts monts), the heat, and the humidity, and how I will crave the golds and reds and chill of autumn. And when the leaves are gone, and "stick season" is upon us, I will wait for the first snow, feel disappointed when it melts, and long for the time when the landscape is entirely covered in white.

And then when the days start to get longer, I will look outside in the morning, frowning and tapping my foot, muttering about the blasted weather and wondering when I can put away the humidifier that hums in our living room from October through March and has to be refilled, it seems, every five minutes (not yet). Wondering when I can throw my parka in the washing machine and hang it in the closet until next fall (not yet).Wondering when I can take the three geraniums that I have watered and misted and kept under a light out to the porch (not yet!).

This is so not-Zen, I know. Maybe it explains why Buddhism is popular in places without seasons, like India and California. Here, practically next door to the pole, Nature herself gives us permission to desire, at certain times of the year, what is still in the future. As soon as spring arrives for good, I'll gladly go back to being fully in the present. But not yet.