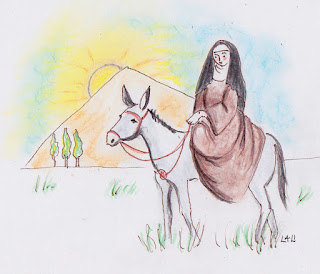

When she was seven, the future Saint Teresa ran away with her brother to seek martyrdom among the Moors in Africa. An uncle found them outside the city walls of Avila and dragged them home. Later, as a Carmelite nun, she crisscrossed Spain on muleback, cleaning up corrupt convents, founding new ones, and doing battle against resistant clerics. And all the while she was writing masterpieces of literature that endure to this day, making friends with that other great mystic and writer, Saint John of the Cross, and having ecstatic visions of God.

Although she'd been dead for four centuries, Teresa's power radiated all the way through the chalk dust in our classrooms and the ink stains in our uniforms."She was a mystic, a writer, a reformer, a theologian, and a doctor of the Church," the teacher told us "even though she was ONLY A WOMAN!"

For us, Teresa was a no-nonsense saint, grown-up and bold, with none of the sickly prettiness of the little virgin martyrs (Lucy, Agnes, Margaret, Cecilia, etc.) whose main merit seemed to consist in their refusal to have sex. In the 1950s, a decade that revered domesticity, and in a culture where virginity, followed by marriage and motherhood, were practically the only options for women, Saint Teresa showed us a different picture of how to be a woman: brave, intelligent, determined, a leader of women and men.

If Teresa of Avila had been the only model held up for our admiration, all would have been well. But in counterpoint to the bold image of the saint we were offered a list of tamer, more "feminine" virtues: we were urged to be patient and humble, and to always think of others before ourselves. Unquestioning obedience was at the top of the list, as was the strictest chastity. "When you go to bed at night," I remember one of my German nuns advising us, "do not let your hands wander all over your body." (Years later, my college roommate said I was the only person she knew who fell asleep with her arms straight at her side, like a corpse in a casket.)

But it was that trio--humility, selflessness, and obedience--that was the most effective at quashing our girlish spirits. How could we nine- and ten-year-olds reconcile those ego-stifling virtues with the drive and assertiveness that Saint Teresa must have possessed in order to achieve all that she did?

It was a dilemma that we were too young to solve, and it caused us much confusion and uncertainty.

It was not altogether bad to have our vision of the indomitable aspects of Saint Teresa's character tempered with the milder virtues. But I shudder to imagine what life would have been like for us girls without the image of the great Saint fighting for justice, writing books, founding convents and monasteries. Years before we heard of Simone de Beauvoir, Betty Friedan, and Gloria Steinem we had Saint Teresa of Avila, in her sandals and brown habit, riding her mule in all weathers, showing us what a woman could be.

Wednesday, May 29, 2019

Wednesday, May 22, 2019

Of Birds And Lilies

"Look at the birds of the air," Father Molloy intoned in his Irish brogue. "They neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns, yet the Lord God feeds them." Then he then went on about lilies and King Solomon, and when he had finished reciting he twinkled his blue eyes and said "Class, I want you to memorize this passage by tomorrow." The blood froze in my veins.

At home that evening I got out the New Testament and my paperback Spanish-English dictionary and went to work. I had no idea what the passage was about. I didn't know the meaning of sow, reap, gather, or barns. Then came the part about the lilies, which neither toil nor spin, whatever that was, but even Solomon was not arrayed like one of them. Arrayed--was it a good or a bad thing not to be arrayed like a lily?

And then a few lines further down Jesus said, "Therefore, do not worry..." (Matthew 6:26-34)

How could I not worry, when I had to memorize that long passage by tomorrow and I didn't know most of the words in it? I looked up sow, and reap, and gather. But by the time I got to barns I was confused. I had seen plenty of sowing and reaping in my grandparents' farm in Catalonia, but as far as I knew, the birds of the air were a menace around harvest time. They did not wait for the Lord God to feed them, but helped themselves boldly to the grain.

I ground my teeth and soldiered on, looking up word after word, but when I put them all together, the passage still didn't make sense. And here it was, almost bedtime, and I hadn't even begun to memorize.

"Therefore, do not worry..."

At fourteen, newly arrived in the U.S. and possessed only of the few crumbs of English I'd acquired from a German teacher during my three years in Quito, I worried all the time. I was the first-ever foreign student in a Catholic high school in Birmingham, Alabama, long before the days when English as a second language became an academic subject. I suspect that nobody knew what to do with me.

For my part, my all-consuming goal was to blend in so I could catch my breath and figure out, without letting anyone notice my ignorance, things I'd never encountered before, like homerooms and assemblies and rallies and football games, and to acquire enough English to survive.

My efforts at camouflage must have worked, because from day one my teachers seemed to assume that I was no different from my classmates. I'm sure that if I'd asked for help it would have been given gladly, but I never asked. I believed, given the stern regimes of my schools in Barcelona and later in Quito, that any sign of weakness or ignorance would be pounced upon by the school authorities and I would be cast into the outer darkness, to spend the rest of my days cleaning bathrooms for a living.

If I had only known how comparatively lenient and indulgent American educators were, I would have relaxed, but I didn't know, so I anxiously continued to mask my deficiencies. Arriving home in the afternoon, after a day of straining with every fiber to understand what was going on in class, I would retire to bed with a headache. Later I would get up and, dictionary in hand, try to do my homework.

But on the night of my encounter with the birds and the lilies, I finally realized that the dictionary was in fact hampering my efforts to understand. It was slowing me down, interrupting the flow of ideas so that I was missing the gist of the passage. Besides, there were just too many words I didn't know. It was impossible to look them all up, let alone remember them. I would simply have to figure out the meanings from the context.

With a sigh, I put the dictionary away and never opened it again. Somehow I winged it, lexicon-less, through the rest of school. At college graduation, my husband-to-be presented me with a hardcover Merriam-Webster Collegiate, but by then I hardly needed it.

It's been a late spring in Vermont, and the birds of the air and the lilies of the field are busy making up for lost time. The words in the Matthew passage are no longer a mystery to me. But, having learned to fret early on, it's those other words of Jesus that I still struggle with, "Therefore, do not worry...."

At home that evening I got out the New Testament and my paperback Spanish-English dictionary and went to work. I had no idea what the passage was about. I didn't know the meaning of sow, reap, gather, or barns. Then came the part about the lilies, which neither toil nor spin, whatever that was, but even Solomon was not arrayed like one of them. Arrayed--was it a good or a bad thing not to be arrayed like a lily?

And then a few lines further down Jesus said, "Therefore, do not worry..." (Matthew 6:26-34)

How could I not worry, when I had to memorize that long passage by tomorrow and I didn't know most of the words in it? I looked up sow, and reap, and gather. But by the time I got to barns I was confused. I had seen plenty of sowing and reaping in my grandparents' farm in Catalonia, but as far as I knew, the birds of the air were a menace around harvest time. They did not wait for the Lord God to feed them, but helped themselves boldly to the grain.

I ground my teeth and soldiered on, looking up word after word, but when I put them all together, the passage still didn't make sense. And here it was, almost bedtime, and I hadn't even begun to memorize.

"Therefore, do not worry..."

At fourteen, newly arrived in the U.S. and possessed only of the few crumbs of English I'd acquired from a German teacher during my three years in Quito, I worried all the time. I was the first-ever foreign student in a Catholic high school in Birmingham, Alabama, long before the days when English as a second language became an academic subject. I suspect that nobody knew what to do with me.

For my part, my all-consuming goal was to blend in so I could catch my breath and figure out, without letting anyone notice my ignorance, things I'd never encountered before, like homerooms and assemblies and rallies and football games, and to acquire enough English to survive.

My efforts at camouflage must have worked, because from day one my teachers seemed to assume that I was no different from my classmates. I'm sure that if I'd asked for help it would have been given gladly, but I never asked. I believed, given the stern regimes of my schools in Barcelona and later in Quito, that any sign of weakness or ignorance would be pounced upon by the school authorities and I would be cast into the outer darkness, to spend the rest of my days cleaning bathrooms for a living.

If I had only known how comparatively lenient and indulgent American educators were, I would have relaxed, but I didn't know, so I anxiously continued to mask my deficiencies. Arriving home in the afternoon, after a day of straining with every fiber to understand what was going on in class, I would retire to bed with a headache. Later I would get up and, dictionary in hand, try to do my homework.

But on the night of my encounter with the birds and the lilies, I finally realized that the dictionary was in fact hampering my efforts to understand. It was slowing me down, interrupting the flow of ideas so that I was missing the gist of the passage. Besides, there were just too many words I didn't know. It was impossible to look them all up, let alone remember them. I would simply have to figure out the meanings from the context.

With a sigh, I put the dictionary away and never opened it again. Somehow I winged it, lexicon-less, through the rest of school. At college graduation, my husband-to-be presented me with a hardcover Merriam-Webster Collegiate, but by then I hardly needed it.

It's been a late spring in Vermont, and the birds of the air and the lilies of the field are busy making up for lost time. The words in the Matthew passage are no longer a mystery to me. But, having learned to fret early on, it's those other words of Jesus that I still struggle with, "Therefore, do not worry...."

Wednesday, May 15, 2019

Not Forest.Trees!

I am married to a man who pays attention to trees. Me, I'm a forest gazer. I stand on a mountain and take in acres of green, stretching all the way to the sea.

In reality, he can barely tell a weeping willow from a sugar maple, and my most interesting forest experience was when I got lost in the woods behind my house. What I'm saying is that my spouse (who can't see the forest for the trees) focuses on the concerns of the moment, whereas I (who can't see the trees for the forest) am forever taking the larger view.

Can you guess which of us is the more serene, contented, and at peace?

Some people are born with a Zen-like instinct for paying attention to the here and now. If I ever had this instinct, it was taken away by the evil fairies at my christening. Since childhood I have embodied that saying of Thich Nhat Hanh's: "I think; therefore, I am not here."

Where am I? I'm on the mountain, staring at the forest, scrutinizing the horizon for threatening hordes, peering among those distracting trees for signs of lions, tigers, and bears. This does not fill me with feelings of security or contentment. Although the view is occasionally neutral, most often it inspires dread: there is too much to do; where do I even start? What if there's a flood, a fire, a war?

Tired of contemplating forests and paying for it with endless hours of unnecessary worry, I'm trying to break the habit.

As if in answer to my need, the universe, via Google, sent me this from Sir William Osler (1849-1919), revered physician and all around good guy: "Think not of the amount to be accomplished, the difficulties to be overcome, or the end to be attained, but set earnestly at the little task at your elbow, letting that be sufficient for the day."

The little task at my elbow! Who could resist? I don't need to cope with a forest stretching across continents, but with a single tree, perhaps a seedling, in need of water and light. Even I can manage that! And in the process, I can take in Sister Tree in all her uniqueness--the feel of the bark, the angle of the branches, the way the leaves move in the breeze--and let that be sufficient for the day.

In reality, he can barely tell a weeping willow from a sugar maple, and my most interesting forest experience was when I got lost in the woods behind my house. What I'm saying is that my spouse (who can't see the forest for the trees) focuses on the concerns of the moment, whereas I (who can't see the trees for the forest) am forever taking the larger view.

Can you guess which of us is the more serene, contented, and at peace?

Some people are born with a Zen-like instinct for paying attention to the here and now. If I ever had this instinct, it was taken away by the evil fairies at my christening. Since childhood I have embodied that saying of Thich Nhat Hanh's: "I think; therefore, I am not here."

Where am I? I'm on the mountain, staring at the forest, scrutinizing the horizon for threatening hordes, peering among those distracting trees for signs of lions, tigers, and bears. This does not fill me with feelings of security or contentment. Although the view is occasionally neutral, most often it inspires dread: there is too much to do; where do I even start? What if there's a flood, a fire, a war?

Tired of contemplating forests and paying for it with endless hours of unnecessary worry, I'm trying to break the habit.

As if in answer to my need, the universe, via Google, sent me this from Sir William Osler (1849-1919), revered physician and all around good guy: "Think not of the amount to be accomplished, the difficulties to be overcome, or the end to be attained, but set earnestly at the little task at your elbow, letting that be sufficient for the day."

The little task at my elbow! Who could resist? I don't need to cope with a forest stretching across continents, but with a single tree, perhaps a seedling, in need of water and light. Even I can manage that! And in the process, I can take in Sister Tree in all her uniqueness--the feel of the bark, the angle of the branches, the way the leaves move in the breeze--and let that be sufficient for the day.

Labels:

anxiety

,

forest

,

Thich Nhat Hanh

,

trees

,

William Osler

,

Zen Buddhism

Friday, May 10, 2019

Bisou's TV Interview

I never knew she was such a publicity hound, but she sure did like the camera: https://www.wcax.com/content/news/Dog-walking-group-at-Wake-Robin-gets-more-seniors-outside-509741431.html

Wednesday, May 8, 2019

Writer, Interrupted

The year my first daughter was born, I wrote my dissertation. I had spent the previous nine months researching and then making an excruciatingly detailed outline of the project. The outline consisted of a complex system of index cards arranged by topics, sub-topics, and sub- sub-topics, each one bound by a rubber band and grouped with others in its category by a larger rubber band.

Having heard that babies could be time consuming, I figured that if I had just fifteen minutes to spare, I could remove the rubber band from a single sub-topic and write a paragraph or two before the next diaper change.

Besides the baby, I had a temporary part-time job teaching in a private school. Thanks to my rubber bands, I nevertheless managed to write all but the last chapter of my dissertation. Since by that point my daughter was no longer nursing every five minutes, my mother came up one weekend and babysat while I went to the library to finish the job.

I found a carrel in a quiet corner, took out the final batch of index cards, snapped off the rubber band and looked around. This being Saturday morning, the stacks were empty. There was no one, not even a mouse, to disturb me. I could concentrate to my heart's content....

Except I couldn't. Somehow I was unable to sustain mental effort for more than fifteen or twenty minutes at a stretch. Motherhood had worked a weird kind of interval training on my brain, so that I needed frequent interruptions in order to function.

Despite the weirdness of those two silent days, I did manage to sweat out the last chapter--but, ironically, it was the only one that my advisor asked me to rewrite.

In Silences, her heart-wrenching book about why writers don't write, Tillie Olsen says,"More than in any other human relationship, overwhelmingly more, motherhood means being instantly interruptible, responsive, and responsible." These days, fatherhood may in some cases get in the way of writing as well, but it's still mostly motherhood that keeps writers from writing.

No matter how talented the writer, it's hard to produce a masterpiece in fifteen-minute stretches. A middle-class mother may well have a physical room of her own, but where to escape the moral obligation, let alone the inborn desire to satisfy a child's endless need for food, company, stimulation, love?

The German poet Rilke was so leery of the drain that affections impose on a writer that he could not live in the same house with his wife and baby. He couldn't even bear to have a dog: "Anything alive that makes demands, arouses in me an infinite capacity to give it its due, the consequences of which completely use me up." (Rilke quoted by Olsen, in Silences.)

For me, the days of index cards and rubber bands were followed by decades of further interruptions, by growing children, work, and life in general. But my present schedule is one to make struggling would-be writers faint with envy: I could, if I wanted to, write uninterruptedly from dawn to dusk, every single day.

But not quite. For as soon as the opening fanfare of Windows announces that I've sat down to write, the cat Telemann comes rushing up to investigate. He sits on the desk, rearranges my papers, sniffs my coffee, and reaches out his white paw to tap on the keyboard (he's been known to delete important stuff). Is he bored, I wonder? Hungry? In need of affection? Poor thing, he never gets to go outside--I should play with him a while.

My little red dog Bisou, less intrusive now than in her youth, is content to sleep in the room while I write--until she starts to wonder when we're going for our walk, or if it's almost dinnertime. She's been with me through thick and thin for the past decade, her entire tiny life. How can I deny her?

My two goldfish and my houseplants are less vocal in their demands, but I can't bear to see them languish. The fish must be fed breakfast and dinner, and the water in their tub changed regularly. The plants need water--not too much--and food and grooming, and carefully placed full-spectrum lights.

Clearly, my brain is still on its old schedule. After fifteen or twenty minutes of writing, it looks around for interruptions. What--no phone calls, no emails, no appointments, nobody at the door? It must be time to walk the dog.

Short of infants of my own, I have hobbled myself with a set of living beings that arouse in me that infinite capacity to give them their due. Rilke would say I'm committing creative suicide.

And so I walk the dog, and play with the cat, and I try not to beat myself up about it. Fifteen or twenty minutes of writing is better than nothing, after all. Despite his richly emotive poetry, Rilke strikes me as a little cold. Besides, who's to say that a well-loved creature is less precious than a great poem?

Having heard that babies could be time consuming, I figured that if I had just fifteen minutes to spare, I could remove the rubber band from a single sub-topic and write a paragraph or two before the next diaper change.

Besides the baby, I had a temporary part-time job teaching in a private school. Thanks to my rubber bands, I nevertheless managed to write all but the last chapter of my dissertation. Since by that point my daughter was no longer nursing every five minutes, my mother came up one weekend and babysat while I went to the library to finish the job.

I found a carrel in a quiet corner, took out the final batch of index cards, snapped off the rubber band and looked around. This being Saturday morning, the stacks were empty. There was no one, not even a mouse, to disturb me. I could concentrate to my heart's content....

Except I couldn't. Somehow I was unable to sustain mental effort for more than fifteen or twenty minutes at a stretch. Motherhood had worked a weird kind of interval training on my brain, so that I needed frequent interruptions in order to function.

Despite the weirdness of those two silent days, I did manage to sweat out the last chapter--but, ironically, it was the only one that my advisor asked me to rewrite.

In Silences, her heart-wrenching book about why writers don't write, Tillie Olsen says,"More than in any other human relationship, overwhelmingly more, motherhood means being instantly interruptible, responsive, and responsible." These days, fatherhood may in some cases get in the way of writing as well, but it's still mostly motherhood that keeps writers from writing.

No matter how talented the writer, it's hard to produce a masterpiece in fifteen-minute stretches. A middle-class mother may well have a physical room of her own, but where to escape the moral obligation, let alone the inborn desire to satisfy a child's endless need for food, company, stimulation, love?

The German poet Rilke was so leery of the drain that affections impose on a writer that he could not live in the same house with his wife and baby. He couldn't even bear to have a dog: "Anything alive that makes demands, arouses in me an infinite capacity to give it its due, the consequences of which completely use me up." (Rilke quoted by Olsen, in Silences.)

For me, the days of index cards and rubber bands were followed by decades of further interruptions, by growing children, work, and life in general. But my present schedule is one to make struggling would-be writers faint with envy: I could, if I wanted to, write uninterruptedly from dawn to dusk, every single day.

But not quite. For as soon as the opening fanfare of Windows announces that I've sat down to write, the cat Telemann comes rushing up to investigate. He sits on the desk, rearranges my papers, sniffs my coffee, and reaches out his white paw to tap on the keyboard (he's been known to delete important stuff). Is he bored, I wonder? Hungry? In need of affection? Poor thing, he never gets to go outside--I should play with him a while.

My little red dog Bisou, less intrusive now than in her youth, is content to sleep in the room while I write--until she starts to wonder when we're going for our walk, or if it's almost dinnertime. She's been with me through thick and thin for the past decade, her entire tiny life. How can I deny her?

My two goldfish and my houseplants are less vocal in their demands, but I can't bear to see them languish. The fish must be fed breakfast and dinner, and the water in their tub changed regularly. The plants need water--not too much--and food and grooming, and carefully placed full-spectrum lights.

Clearly, my brain is still on its old schedule. After fifteen or twenty minutes of writing, it looks around for interruptions. What--no phone calls, no emails, no appointments, nobody at the door? It must be time to walk the dog.

Short of infants of my own, I have hobbled myself with a set of living beings that arouse in me that infinite capacity to give them their due. Rilke would say I'm committing creative suicide.

And so I walk the dog, and play with the cat, and I try not to beat myself up about it. Fifteen or twenty minutes of writing is better than nothing, after all. Despite his richly emotive poetry, Rilke strikes me as a little cold. Besides, who's to say that a well-loved creature is less precious than a great poem?

Labels:

cats

,

dogs

,

fantail goldfish

,

motherhood

,

Rainer Maria Rilke

,

Silences

,

Tillie Olsen

,

women writers

,

writer's block

,

writers

,

writing distractions

Wednesday, May 1, 2019

Sister Squirrel

As with most people who feed the birds, my relationship with the gray squirrel oscillates between grudging tolerance and rodenticidal rage. There is no lack of stories about the squirrel's diabolical cleverness in getting at food intended for the birds, so I won't bore you with mine. I'll simply say that when one of these plump uninvited guests goes anywhere near my bird feeders, I grit my teeth in aggravation.

Yet it wasn't always like this. When I first lived in an American suburb, I found the squirrels adorable, with their slanted eyes, monkey-like hands, and those cloud-colored tails that morphed into a question mark the minute they sat still. I thought they were charming and exotic, and I couldn't understand why so many people disliked them.

Now I do. I've been feeding birds and fighting squirrels for longer than we've been at war with Afghanistan, with mixed results. I've been wondering lately if it might not be time to change my attitude. Life's too short for hatred and strife.

The story of Saint Francis and the wolf of Gubbio comes to mind. There lived in the forests around Gubbio a fierce wolf who killed sheep, shepherds, and any citizen who ventured outside the city walls. One day Francis went in search of the wolf. He found him gnawing on a thigh bone and said, "Brother Wolf, why so much killing?"

"Winter is hard in the forest, Brother Francis," the wolf responded, "and I was hungry."

Francis made a deal with the wolf: if he promised never to harm livestock or people again, he would get the townspeople to feed him so that he would not go hungry. The wolf gave Francis his paw in agreement, and the people of Gubbio and their wolf lived in harmony ever after.

Like the wolf, my squirrels are hungry. Why should I begrudge them a few pounds of sunflower seeds, some measly suet cakes? Why not let them share the banquet that I so prodigally set out for the birds?

Maybe I'm afraid that, if I let the squirrels come to my feeders, more and more of them will arrive--huge invading caravans of squirrels that will drive the birds away and me into bankruptcy. Maybe I should build a wall around my feeders, a really high wall topped with barbed wire. Maybe, just to make sure, my husband and I should take turns standing guard with a pellet gun....

Or maybe I could go and stand beside the feeders and make a speech to the squirrels.

"Little gray Sisters," I would say, "welcome to my backyard. Here are my bird feeders. Here is my birdbath. You are welcome to all the water you can drink, and to the seeds that fall on the ground.

"I would prefer it if you didn't climb onto the feeders and dig out wasteful amounts of seed and suet, but I understand that some of you may not be able to resist the temptation. Whatever. The world is wide enough for your kind and mine and the titmice and chickadees, finches and woodpeckers.

"I will now go inside, take a deep breath, and try to see the beauty and innocence in your agility and determination. Pay no attention to the gray cat batting at you on the other side of the glass. He's never allowed outdoors."

Yet it wasn't always like this. When I first lived in an American suburb, I found the squirrels adorable, with their slanted eyes, monkey-like hands, and those cloud-colored tails that morphed into a question mark the minute they sat still. I thought they were charming and exotic, and I couldn't understand why so many people disliked them.

Now I do. I've been feeding birds and fighting squirrels for longer than we've been at war with Afghanistan, with mixed results. I've been wondering lately if it might not be time to change my attitude. Life's too short for hatred and strife.

The story of Saint Francis and the wolf of Gubbio comes to mind. There lived in the forests around Gubbio a fierce wolf who killed sheep, shepherds, and any citizen who ventured outside the city walls. One day Francis went in search of the wolf. He found him gnawing on a thigh bone and said, "Brother Wolf, why so much killing?"

"Winter is hard in the forest, Brother Francis," the wolf responded, "and I was hungry."

Francis made a deal with the wolf: if he promised never to harm livestock or people again, he would get the townspeople to feed him so that he would not go hungry. The wolf gave Francis his paw in agreement, and the people of Gubbio and their wolf lived in harmony ever after.

Like the wolf, my squirrels are hungry. Why should I begrudge them a few pounds of sunflower seeds, some measly suet cakes? Why not let them share the banquet that I so prodigally set out for the birds?

Maybe I'm afraid that, if I let the squirrels come to my feeders, more and more of them will arrive--huge invading caravans of squirrels that will drive the birds away and me into bankruptcy. Maybe I should build a wall around my feeders, a really high wall topped with barbed wire. Maybe, just to make sure, my husband and I should take turns standing guard with a pellet gun....

Or maybe I could go and stand beside the feeders and make a speech to the squirrels.

"Little gray Sisters," I would say, "welcome to my backyard. Here are my bird feeders. Here is my birdbath. You are welcome to all the water you can drink, and to the seeds that fall on the ground.

"I would prefer it if you didn't climb onto the feeders and dig out wasteful amounts of seed and suet, but I understand that some of you may not be able to resist the temptation. Whatever. The world is wide enough for your kind and mine and the titmice and chickadees, finches and woodpeckers.

"I will now go inside, take a deep breath, and try to see the beauty and innocence in your agility and determination. Pay no attention to the gray cat batting at you on the other side of the glass. He's never allowed outdoors."

Labels:

bird behavior

,

bird feeders

,

birds

,

immigration

,

Saint Francis of Assissi

,

squirrel behavior

,

squirrels

,

the wolf of Gubbio

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)

Followers

My Blog List

-

-

Fans or hooligans?1 month ago

-

Three Days in June by Anne Tyler4 months ago

-

Self Portrait.3 years ago

-

-